Attempts to harmonize forestry and land use planning – new dispute about flying squirrel

After removal of the legal requirement to establish the boundaries of areas where Siberian flying squirrels are found, special landscaping permits have been demanded for work in such areas. However, the legislation stipulates that landscaping permits can only be required due to landscape changes.

The requirement to establish the boundaries of areas where Siberian flying squirrels (Pteromys volans) are found was removed because it was considered to bring little benefit compared to the work it caused. Removing the requirement does not decrease the protection rate of the flying squirrel.

However, in connection with the “Forestry land and land use planning” exercise at the Ministry of the Environment it was found that after the requirement was lifted, some regional Centres for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment have begun to demand landscaping permits for carrying out work in areas with flying squirrels.

Municipal authorities, which are in charge of general land use planning, may require a landscaping permit if they consider, for example, that harvesting trees may cause excessive damage to the landscape.

Landscaping permits are based on the Land Use and Building Act, which says that activities that change the landscape may be subject to a permit, but the same does not apply to the protection of biodiversity. The forest sector considers that the demands of the environmental authorities stretch the interpretation of the Act too far.

According to Mr. Harry Berg, Environment Counsellor at the Ministry of the Environment, who is in charge of the ”Forestry land and planning” work in the Ministry, guidelines for the protection of the Siberian flying squirrel were published by the Ministry on 12 May 2016 – that is, after the requirement to establish the boundaries of flying squirrels’ nesting and resting areas had been removed.

The guidelines contain a chapter on the harmonising of nature protection and general land use planning, but no mention of landscaping permits – neither in this particular chapter nor elsewhere in the guideline.

Much room for improvement

The objective of the ”Forestry land and planning” work is to clarify the relation between forestry and general land use planning, in order to find out whether land use planning places inappropriate constraints on forestry and whether all related norms are necessary.

The work serves as background material for a task force which is scheduled to submit a proposal for amendments to the Land Use and Building Act by the end of May.

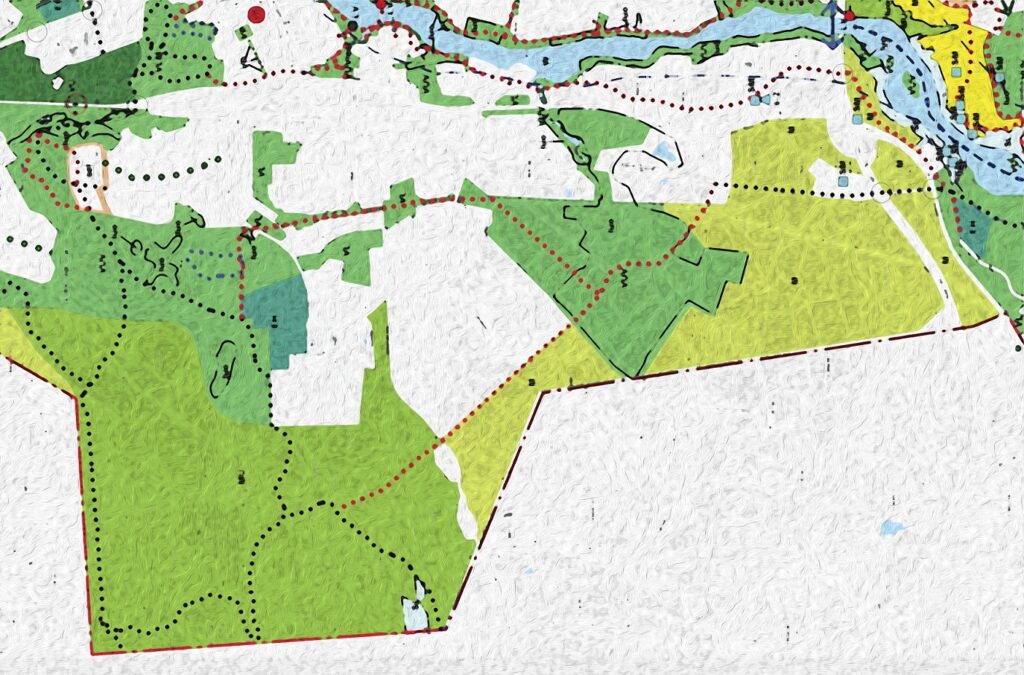

Four objects of improvements have been identified: landscaping permits, instructions and markings entered on maps in the connection of land use planning, evaluation of the impact of land use planning and compensation practices.

As regards landscaping permits, the problem for a forest owner is that the permit often sets constraints on forestry operations, yet compensation for financial loss is very hard to get. What is more, the owner must pay for the permit, and the price is so high that it may consume all revenue from the forestry operation.

Since even negative permits have to be paid for, forest owners sometimes do not even apply for one and opt for not harvesting their forest.

The forest sector demands that the need for landscaping permits is removed in areas covered by the Forestry Act. Another option would be to just develop the procedure to remove obvious weaknesses.

New markings related to land use planning add confusion

A general observation on map markings related to land use planning is that their number is increasing, as is the area to which they apply. In addition to this, their meaning is often unclear.

One and the same marking may mean different things in different parts of the country, and the markings are not compatible with general information systems. This is proposed to be corrected.

Some land use planners consider that the impact of land use planning are sometimes evaluated even too minutely. On the other hand, some impacts are not evaluated at all.

”Take windmills, for example. Their impact on landscape, nature and environmental values is evaluated, but not those on livelihoods giving way for windmills. This is something that even the planners themselves do admit,” says Ms. Niina Riissanen, Senior Inspector at the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry and a member of the working group.

Evaluating the impact is also not very easy. Consequently, the Natural Resources Institute Finland is developing a tool for this.

Forest owners are encouraged to participate in land use planning

Riissanen points out that a land use plan may not cause unreasonable harm to the landowner. The Land Use and Building Act contains provisions on compensation, but the threshold for receiving any is inordinately high.

Neither are there practices for awarding compensations, since it seems that nobody has ever demanded compensation for losses caused by land use planning in a court of law. The remedies proposed are few: the work suggests that ”eventual compensation cases” be monitored.

Riissanen encourages forest owners to participate in land use planning. This is also the standpoint adopted by the family forest owners’ union in Finland, the MTK.

Then again, the word is that forest owners are sometimes excluded from the planning processes just because they are forest owners. Both Berg and Riissanen find this unacceptable.

”It is understandable that they cannot make the final decisions on plans concerning their own forests,” says Riissanen, ”but there are clear provisions in the Land Use and Building Act that give the owners the right to participate.”

Kirjoita kommentti