Professor Pekka Kauppi: Forest use must be examined over a long period

During the confusing and populistic LULUCF debate in 2017, conceptions used to argue for restrictions of forest use were not based on sustainable climate or forest policy, says Professor Pekka Kauppi. At worst, the present generation advocated stopping the use of forests to mitigate climate change, thus excluding this option not just for themselves, but also for their grandchildren.

According to Pekka Kauppi, Professor of Environmental Science and Policy at the University of Helsinki, the European Union’s final decisions last week, concerning forest use in mitigating climate change, open up a way towards a new and better climate policy. The prospects actually look good: forests are developing in a good direction globally.

Carbon emissions from forest loss are decreasing at a good pace in the tropics, too, while the use of timber resources is increasing and becoming more and more rational. Forest management produces good results not only in the industrialized countries, but also frequently in subtropical and temperate regions, such as Uruguay and China.

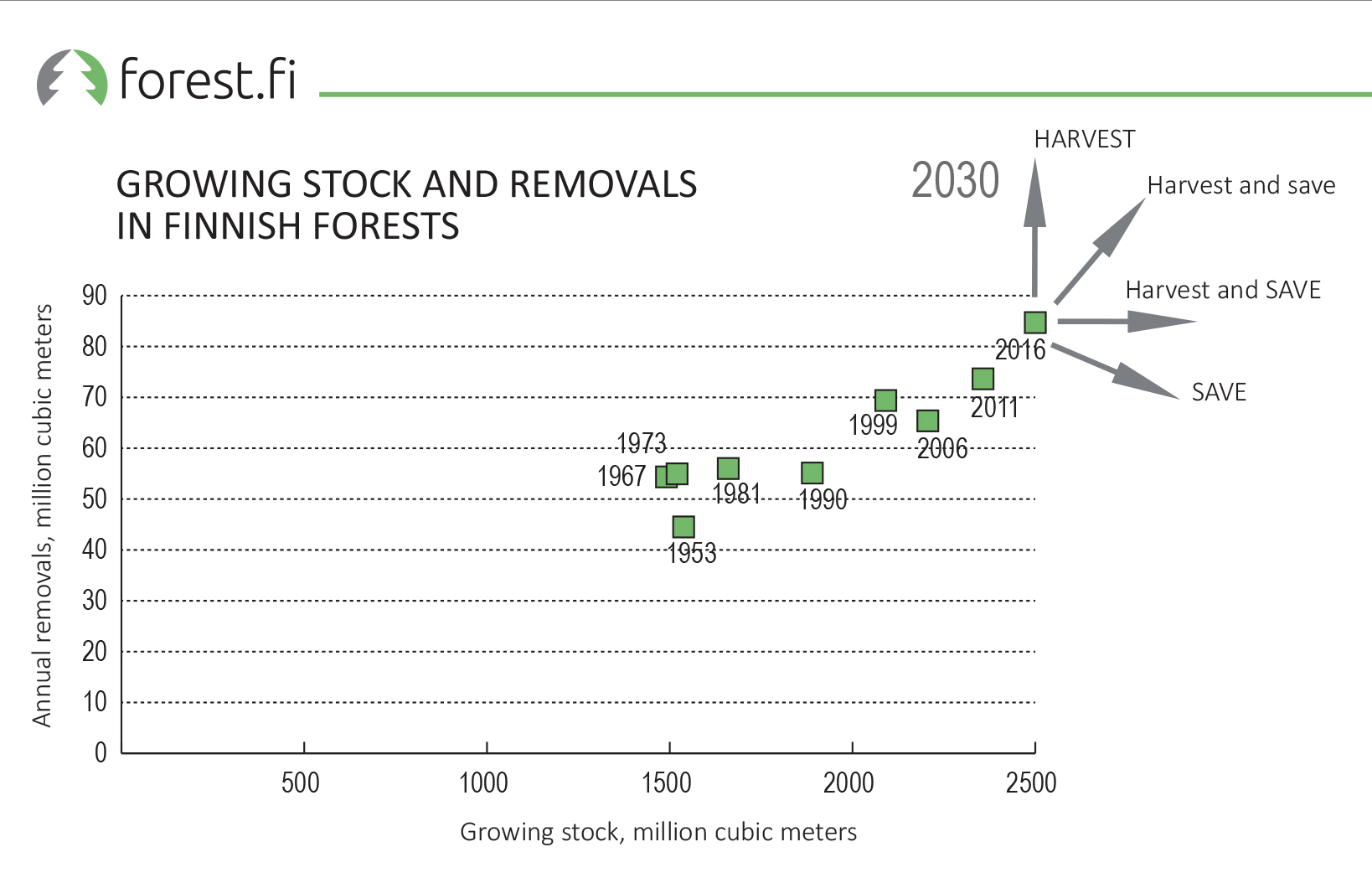

“Although the global forest area will continue to decrease for some years, the volume of timber stock has taken an upward turn,” writes Kauppi in his publication Metsät ja ilmastopolitiikka [Forests and climate policy, published only in Finnish], updating the findings in the pamphlet To Harvest or to Save from 2014.

Harvesting restrictions would increase emissions

Compared to 2014, Kauppi has one new and important message, about the connection between Finland’s timber harvesting and global markets.

In last year’s debate it was put forward that Finland should decrease its logging volumes in order to increase the carbon storage in its forests. This was demanded particularly because of the need to start decreasing the amount of atmospheric carbon very quickly, before 2050.

Kauppi admits that this would have increased the carbon storage in Finnish forests, but instead of improving the atmospheric carbon balance, the effect would have been the opposite. This is because the demand for forest use in Finland is global.

“If we restrict the use of Finnish forests, the demand will turn to somewhere else. There is recent research data on this,” says Kauppi.

According to Kauppi, regardless of where the somewhere else would have been, the forestry operations would very probably have been less efficient than in Finland. This would ultimately have led to even larger harvest volumes.

Not all timber products are marketed globally, however. “Take energy production, for example. We could very well stop harvesting stumps for energy production without increasing any kind of harvesting elsewhere,” says Kauppi.

Decreasing atmospheric carbon is not a snap job

Kauppi also points out that however much we would like it, it is impossible to make the level of atmospheric carbon decrease before 2050. “Bearing in mind the previous years when the emissions have only accelerated, this simply cannot be done,” says Kauppi.

This is why we need to take a longer perspective on this, also when it comes to forests.

However, the Paris climate agreement of 2015 allows each country to select the most appropriate means of reaching the decrease in emissions. In the case of Finland, the use of forests is a natural solution.

“Britain and the Netherlands, for example, depend on imported timber products. They don’t have the same need to develop forest know-how as we do,” says Kauppi.

During the logging debate it was demanded that carbon sequestration should be permanently prioritised in forest use. Kauppi considers that this could be done in countries where forests are less significant for the production of well-being than in Finland.

However, an essential feature of sustainable development is that no single dimension of sustainability may cancel out the others. If this happens, all of sustainability will be lost. Putting carbon sequestration above everything else would mean precisely this.

In addition, it would contradict the most important principle of sustainability, which says that we may not ruin the opportunities of our grandchildren – in this case, of using the forests. “This is exactly what we would do if we responded to climate change by stopping to use the forests,” says Kauppi.

Moreover, the means would become ineffective in very short order, because natural forest does not sequester carbon forever. If it did, there would be no limit to how much biomass could be accumulated in forests. “But you don’t see layers of coal forming in natural forests,” says Kauppi.

Then again, starting to use the forest after that would not be possible either, as that would mean releasing the carbon storages into the atmosphere again.

Using large trees instead of small ones makes little sense

Sustainable forestry, on the other hand, provides opportunities for subsequent generations, with the increasing productivity of the forests. At the same time, using the forests may create an even bigger carbon storage than the alternative of not using them.

According to a recent calculation (published only in Finnish) by VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, Aalto University and Natural Resources Institute Finland, the harvesting volumes and the carbon sinks in forests can be maximized by carefully designed methods of forestry. In this way, we could create a carbon storage that is 40 percent larger than the current one in Finnish commercial forests, while maintaining the current level of harvesting.

And once this storage had been created, we could still continue using the forests, just making sure that the carbon storage would not diminish.

Another thing that was contrasted in last year’s logging debate were large and small trees and products made of them. According to Kauppi, thinking of them as mutually exclusive options is not very sensible. It would be about as clever as asking a mint to produce coins with only a heads side because it is better than the tails side.

You cannot use up all of a log for long-lived sawmilling products, because sawmills make angular products and logs are round. After sawmilling, you will always have bark, sawdust and waned timber. The latter, on the other hand, makes very good raw material for pulp, which is sometimes classified as short-lived.

“Then again, if you want to grow stout timber, you will only get enough of it by thinning out smaller trees, to give the remaining trees more space to grow,” says Kauppi.

These smaller trees are the main source of raw material for the pulp industry. You will always have some of them if your purpose is to have large logs.

To Harvest or to Save pamphlet

Kirjoita kommentti